February 28, 2018

Flashback to December 30, 2010. I am training Filipino Martial Arts with my relatively new student James. We are working destruction defenses to common strikes, like jabs and crosses. For those not familiar with this technique, the one on the “defensive” funnels punches from the aggressor into elbow strikes. Even with wrapped and gloved hands, my fist stood no chance against the elbow James delivered. The break of my third metacarpal bone was heard throughout the martial arts school. With approximately a minute left on the ring timer, I had the option of giving up or continuing on. Let’s face it, giving up really isn’t an option. I made do with my “other strong hand” and finished the round. The next morning, my hand was swollen and for the next month and a half, I had to train very differently.

At any moment, we can become injured. Accidents happen and there is simply no good time for one to afflict us. Take a fall in the woods and break your wrist breaking your fall. Slip with you knife and cut your leg. Pay too much attention to the ground and that branch your buddy is holding out of the way hits you in your eye. Accidents suck and injuries suck even more. Many survival instructors have recognized the possibility of accidents and have started to teach one-hand fire starting, one-hand this and one-hand that. Even Les Stroud attempted an injured arm episode of his show Survivorman years ago but ultimately gave up on it during filming. Handicap training isn’t easy and this leads to taking the easy way out of a difficult task or accomplishing only part of a difficult task under the veil of “handicap training.” Sure, you can start a fire with one hand but can you maintain it? You can tie a knot with one hand but can you set up your entire shelter? For this month’s Fiddleback Forge Blog, I’m issuing a challenge. If you want to train with a handicap, don’t sell your skillset short. Train from start to finish with that handicap as you won’t have the option to bail out if it really happens to you in the field.

At any moment, we can become injured. Accidents happen and there is simply no good time for one to afflict us. Take a fall in the woods and break your wrist breaking your fall. Slip with you knife and cut your leg. Pay too much attention to the ground and that branch your buddy is holding out of the way hits you in your eye. Accidents suck and injuries suck even more. Many survival instructors have recognized the possibility of accidents and have started to teach one-hand fire starting, one-hand this and one-hand that. Even Les Stroud attempted an injured arm episode of his show Survivorman years ago but ultimately gave up on it during filming. Handicap training isn’t easy and this leads to taking the easy way out of a difficult task or accomplishing only part of a difficult task under the veil of “handicap training.” Sure, you can start a fire with one hand but can you maintain it? You can tie a knot with one hand but can you set up your entire shelter? For this month’s Fiddleback Forge Blog, I’m issuing a challenge. If you want to train with a handicap, don’t sell your skillset short. Train from start to finish with that handicap as you won’t have the option to bail out if it really happens to you in the field.

Handicapped Fire

Handicapped FireOne of the most popular and important handicapped skills is firestarting. Unfortunately, many survival/bushcraft enthusiasts will only practice sparking a ferro rod with one hand. They will not gather wood, utilize natural forks in trees to break long branches, or create fuzz sticks by driving their knife into a log and pulling the wood along the edge. I applaud people willing to try scraping a ferro rod but I want them to push harder starting their handicapped challenge from the beginning with no materials on hand. Starting the fire is easy, maintaining it is the problem. Carrying large fuel with one hand doesn’t mean you can use the crook of your other elbow as a support. Remember, firecraft has 4 stages; preparation, starting, maintenance, and extinguishing. Don’t fool yourself by assuming starting a fire one-handed is ownership of the whole process. Consider carrying a quality one-handed firestarter if your skill set is improving but not where it should be yet. Plenty of one-handed firestarters are available through Exotac.

The Mundane Tasks

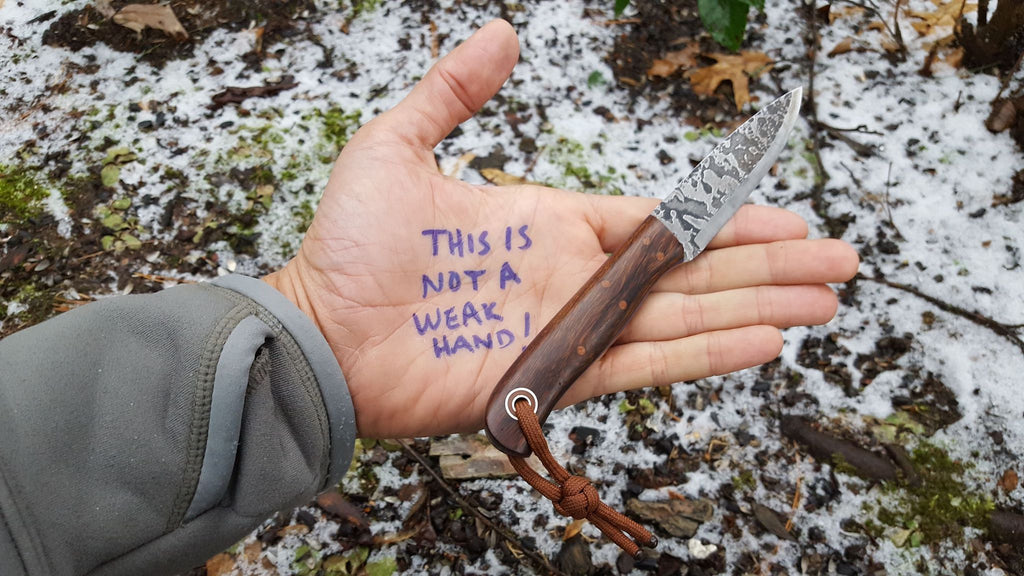

The Mundane TasksWhen my hand was broken, I challenged myself to perform the necessary skills we usually associate with bushcraft and survival training. Once I accomplished fire skills, I moved onto others. What I found most difficult were those basic daily tasks that are normally accomplished with my right hand. Brushing my teeth, tying my tie, everything you could imagine becomes foreign when done with the other side. Think about training your “other strong side” around camp and use it instead of your strong side. Open packages, stir your stew pot, hang your bear bag, sharpen your blade. You’ll find you will pick up on little nuances of each task by learning to do them again. By the way, if you are wondering why “other strong side” is the term I use for my left hand, do you really want to find out if my left is weak? Sayoc Kali has taught me I don’t have a “weak” side and it is a term we use in our training. Words have meaning and words can make you believe something you are not.

When we think handicap, we often assume an injury to one hand. We train one-handed but we fail to recognize other possibilities. An injured hand is one problem but what changes with a broken leg? What changes with loss of an eye? What changes with paralysis from the waist down? These are scenarios that have happened to people before us and they can happen again. In training, we have the luxury of choosing our handicaps and when they start and end. One way around this and to make sure you can’t “game” your solution to a problem is to work with a group and draw folded pieces of paper from containers. One container can have the body part and another can have the skill that must be accomplished. This way, there are many possible scenarios you can run with your training group.

Dealing with the “Handicap”

Dealing with the “Handicap”As real as you want to make your training, in the back of your mind, it is still training. This is where safety and practicality but heads with realism. You want to take your training to the limit but you can’t let your training be more detrimental to you in the long run. What you can work with, even in these mock scenarios, is the correct solution to a problem. One lesson I’ve learned cross training in various martial arts is using your whole body as part of the solution. Striking is less effective without footwork and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu works better when you use all your extremities against just one of your opponent’s. Try using the crook behind your knee to support material as you cut it with one hand. Use your arms to move you around on makeshift crutches if you “injure” a leg. Use your senses of smell and touch to locate the right wood to make fire in the “total blindness” scenario. If one half of your body is injured, don’t make the uninjured part of your body do twice as much work when your whole body can assist.

It’s very convenient to throw out a handicapped challenge when conditions are right. What really tests your ability is training when you are tired, hungry, cold, and in some sort of discomfort. Handicapped training is an example of vertical training. It is a way of making a simple task much more difficult. If your ultimate goal is to become more ready, prepare now. You need not wait for an accident to happen to experience it for the first time. Oh, if you’re wondering if I’m still friends with my training partner James, we absolutely are. Those friends who share blood, sweat, and tears with you are often the strongest you’ll ever have.

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Frequently Asked Questions

Product Warranty Information

Returns & Exchanges

Shipping Policy

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Search

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more…

Fiddleback Forge

5405 Buford Hwy Ste 480

District Leather Bldg

Norcross, GA 30071

© 2025 Fiddleback Forge.

Fiddleback Forge brand name and Logo are registered trademarks of Fiddleback Forge, Inc. All rights reserved.